By Dr. Nure Alam

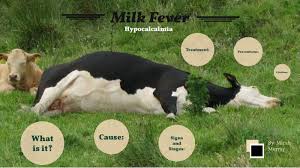

It is an acute to peracute, afebrile, flaccid paralysis of mature dairy cows that occurs most commonly at or soon after parturition due to decreased in serum calcium levels. It is manifest by changes in mentation, depression of consciousness to generalized paresis, muscular weakness & circulatory collapse. The name Milk Fever is a misnomer because symptoms usually not include fever even the animal show sub normal temperature. Species affected- commonly high yielding Cows, sheep and goat also affected.

Pathgogenesis: Dairy cows will secrete 20–30 g of calcium in the production of colostrum and milk in the early stages of lactation. This secretion of calcium causes serum calcium levels to decline from a normal of 8.5–10 mg/dL to <7.5 mg/dL. The sudden decrease in serum calcium levels causes hyperexcitability of the nervous system and reduced strength of muscle contractions, resulting in both tetany and paresis. Parturient paresis may be seen in cows of any age but is most common in high-producing dairy cows entering their third or later lactations. Incidence is higher in Channel Island breeds.

Epidemiology and underlying Factors: Age- generally incidence increases with high milk yielding at 3rd to upward lactations (4-6most). In older cows the ability of ca absorption from intestine due to formation of insoluble salt in intestine and precipitation of dietary indigestible & impermeable materials and mobilization from bone decreased due to parathyroid dysfunction/ insufficiency, decreases ca mobilization in dry period. Excessive loss of Ca in the colostrums and fetal growth at last stage of pregnancy. Insufficient Dietary supplement of Ca, starvation, low Magnesium (Mg) and High Phosphorus (P) in diet reduce ca mobilization.

2

Clinical Findings and Diagnosis: History: History of high milk yield, 3rd to upward lactation, poor nutrition. Parturient paresis usually occurs within 72 hours of parturition. But in field practice same condition found at high milk yielding hypocalcaemic cows before parturition and at Milking stage also. It can contribute to dystocia, uterine prolapse, retained fetal membranes, metritis, abomasal displacement, anorexia, recurrent bloat, agalactia and mastitis.

Clinically Parturient paresis has three discernible stages- Stage I Animals show signs of muscle spasm, hypersensitivity and excitability. Cows may be mildly ataxic, have fine tremors over the flanks and triceps, and display ear twitching and head bobbing. Cows may appear restless, shuffling their rear feet and bellowing. Anorexia, reluctant to move is also common. Temperature may slightly increase. Blood Ca level may be below 7.5mg/dl.

Stage-II Animals are unable to stand but can maintain sternal decumbency. Cows are obtunded, anorectic, and have a dry muzzle, subnormal body temperature, and cold extremities. Auscultation reveals tachycardia and decreased intensity of heart sounds. Peripheral pulses are weak. Smooth muscle paralysis leads to GI stasis, which can manifest as bloat, failure to defecate and loss of anal sphincter tone. An inability to urinate may manifest as a distended bladder on rectal examination may leads to Vaginal prolapsed. Cows often tuck their heads into their flanks, or if the head is extended, an S-shaped curve to the neck may be noted. Blood Ca level may be 3.5 to 6.5mg/dl. The extremities will feel cold, temperature may lower then 1000 F.

3

Stage-III, cows lose consciousness progressively to the point of coma. They are unable to maintain even sternal recumbency, have complete muscle flaccidity, are unresponsive to stimuli, and can suffer severe bloat. Blood Ca level may be 1mg/dl. As cardiac output worsens, heart rate can approach 120 bpm, and peripheral pulses may be undetectable. If untreated, cows in stage 3 may survive only a few hours. Severe bloat developed and Respiratory stress found and may die due to respiratory arrest.

(Differential diagnoses include toxic mastitis, toxic metritis, other systemic toxic conditions, traumatic injury (eg, stifle injury, coxofemoral luxation, fractured pelvis, spinal compression), calving paralysis syndrome (damage to the L6 lumbar roots of sciatic and obturator nerves), or compartment syndrome. Some of these diseases, in addition to aspiration pneumonia, may also occur concurrently with parturient paresis or as complications. And also may lead Bovine Secondary Recumbency to downers cow syndrome.)

Treatment: Treatment is directed toward restoring normal serum calcium levels as soon as possible to avoid muscle and nerve damage and recumbency. Recommended treatment is IV injection of a calcium gluconate salt, although SC and IP routes are also used. A general rule for dosing is 1 g calcium/45 kg (100 lb) body weight. Infield condition it is practiced that IV Ca given with Dextrose Saline, it also supply instant energy and reduce Cardio toxic effect of Ca by lowering Ca concentration as well as risk of Clinical or Sub-clinical Ketosis. Most solutions are available in single-dose, 500-mL bottles that contain 8–11 g of calcium (Cal-D-Mag, Magical-28. Super CMP may given @500ml IV)

4

In large, heavily lactating cows, a second bottle given SC may be helpful, because it is thought to provide a prolonged release of calcium into the circulation. SC calcium alone may not be adequately absorbed because of poor peripheral perfusion and should not be the sole route of therapy. Calcium is cardiotoxic; therefore, calcium-containing solutions should be administered slowly (10–20 min) while cardiac auscultation is performed. If severe dysrhythmias or bradycardia develop, administration should be stopped until the heart rhythm has returned to normal. To prevent cardiac hazards Atropine sulfate may use IM prior IV Saline start. Calcium propionate in propylene glycol gel or powdered calcium propionate (0.5 kg dissolved in 8–16 L water administered as a drench) is effective, less injurious to tissues, avoids the potential for metabolic acidosis caused by calcium chloride, and supplies the gluconeogenic precursor propionate. Oral administration of 50 g of soluble calcium results in ~4g of calcium being absorbed into the circulation. Regardless of the source of oral calcium, it is important to note that cows with hypocalcemia often have poor swallowing and gag reflexes. Care must be exercised during administration of calcium-containing solutions to avoid aspiration pneumonia. Gels containing calcium chloride should not be administered to cows unable to swallow.

Vitamin ADE (Renasol-ADE, Acivit ADE, ES-ADE @10-20ml/animal), Steroids (Predexanol-S, Prednivet @ 10-20ml, IM), Butaphosphan-Cyanocobalamine (Buphos, Vitaphos @1ml/10kgs, IM), Nerve Tonic (Nervin, Neuro-B @1ample/50kgs) may given to Stimulate Metabolism. These medicine commonly practiced in field condition.

Response to Treatment: Hypocalcemic cows typically respond to IV calcium therapy immediately. Tremors are seen as neuromuscular function returns. Improved cardiac output results in stronger heart sounds and decreased heart rate. Return of smooth muscle function results in eructation, defecation, urination & mastication. Approximately 75% of cows stand within 2 hr of treatment. Animals not responding by 4–8 hr should be reevaluated and retreated if necessary. Of cows that respond initially, 25%–30% relapse within 24– 48 hr and require additional therapy. Incomplete milking has been advised to reduce the incidence of relapse. Historically, udder inflation has been used to reduce the secretion of milk and loss of calcium; however, the risk of introducing bacteria into the mammary gland is high.

5

Prevention Historically, prevention of parturient paresis has been approached by feeding low-calcium diets during the dry period. The negative calcium balance results in a minor decline in blood calcium concentrations. This stimulates PTH secretion, which in turn stimulates bone resorption and renal production of 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D. Increased 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D increases bone calcium release and increases the efficiency of intestinal calcium absorption. Although mobilization of calcium is enhanced, it is now known that feeding low-calcium diets is not as effective as initially believed. Furthermore, on most dairy farms today, it is difficult to formulate diets low enough in calcium (<20 g absorbed calcium/cow/day), although the use of dietary straw and calcium-binding agents such as zeolite or vegetable oil may make this approach more useful. Alternative methods to prevent hypocalcemia include delayed or incomplete milking after calving, which maintains pressure within the udder and decreases milk production; however, this practice may aggravate latent mammary infections and increase incidence of mastitis. Prophylactic treatment of susceptible cows at calving may help reduce parturient paresis. Cows are administered either SC calcium on the day of calving or oral calcium gels at calving and 12 hr later. Most recently, the prevention of parturient paresis has been revolutionized by use of the dietary cationanion difference (DCAD), a method that decreases the blood pH of cows during the late prepartum and early postpartum period. This method is more effective and more practical than lowering prepartum calcium in the diet. The DCAD approach is based on the finding that most dairy cows are in a state of metabolic alkalosis due to the high potassium content of their diets. (DCAD Minus-@30gm daily before 1month of Parturition).

Vitamin D metabolites enhance GI calcium absorption, whereas PTH enhances GI calcium absorption and stimulates bone resorption. So before and after parturition administration of Vitamin D reduce the risk and enhance recovery.